One drawback of a 500-year-old cottage with low-beamed ceilings is that people—especially guests—smack their heads a lot. Visitors leave with golf ball–size lumps on their foreheads, and more than once I've had to scrape blood and bits of scalp from the doorjambs. A plus is that with such low ceilings there are no overhead light fixtures. This means that no one can turn them on, much less turn them on and then walk away, leaving a room set with rustic antiques to now look sad and washed-out, like a crime scene in which the weapon was a cudgel. It's funny how with the flick of a switch you can perform a virtual charmectomy: wiping away everything that made a place inviting. Odder still are the people who don't notice. I never knew you were that kind of person, I'll often think, shocked that someone I liked enough to invite into my home turned out to be one of them—a type I know all too well.

If my father were a talking doll, the kind with a ring in his back that, when pulled, caused him to repeat his most often-used phrases, the ones that make him him, the first would be "Turn the damn light on," followed by "Turn that damn light off."

The "off" bit I'm all for. It's one of my trademark phrases as well. I never leave lamps burning in a room that I'm not in. When home alone I've been known to use a flashlight when going from one floor to another. It's not that I'm cheap. Rather, it just seems wasteful. Given the finite amount of natural resources we have left, what's more important, brightening my empty living room for no reason whatsoever or powering the machines preserving the cryonically frozen body of double Triple Crown winner Ted Williams? I'm no baseball fan, but it would be fun to watch someone who died in 2002 thaw out, discover that we have a black president, and die all over again, this time of a heart attack.

When I was growing up, it was my mother who cooked dinner, and my mother who put it on the table. Most often she did the cleaning up as well. Was it that much to ask, then, that she got to eat by her beloved candlelight? "I can't see my damn dinner," my father would complain two seconds after sitting down.

Well, that never stopped José Feliciano, I remember thinking. You know where your plate is, so doesn't it stand to reason that your food is on it?

He'd turn the overhead light on and beneath it we'd all become sallow. The candles burning in their lovely holder were now just cigarette lighters, for my mom at first, and later for just about all of my sisters and me. The moment my father finished eating he would leave the dining room and go downstairs to watch TV. We would then douse the overhead light and spend hours around the table. Our faces were naturally youthful back then, but the added rosiness was a nice touch. As for our mother, she was transformed. Everyone looked better in the soft glow of a candle, and everything as well: the battery-powered grandfather clock, the ceiling with its smoke-stained cottage-cheese finish, the gravy-spattered family portraits displayed atop the buffet; until the overhead light was snapped back on, all of these things were forgiven.

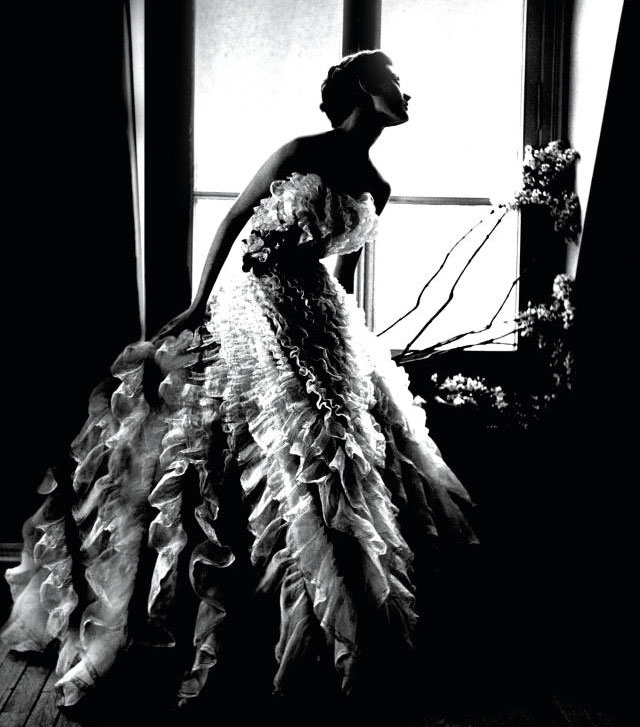

Down in my room it was nothing but lamps, sometimes with scarves draped over the shades, like I was an aging silent-screen goddess rather than a 15-year-old boy with braces on his teeth. During the day it was important to open my curtains just so, and to adjust them according to the time and weather. The best light came late in the day, and in autumn, when it was golden and fell in shafts across the perfectly made bed, I would sometimes get shivers. Do other guys lean against their dressers, admiring the play of sun and shadow on their Gustav Klimt posters?, I'd wonder.

Do other guys lean against their dressers, admiring the play of sun and shadow on their Gustav Klimt posters?

The answer, I learned on my first day of college, was no. My dorm room had cinder-block walls and brutal iron-frame beds. But, still, with candles and the right sorts of lamps, it could be nice, at least in the evening. But no. My roommate, Greg, was the type with only two speeds: pitch-dark, or bright enough to perform surgery. "He closes the blinds to take an afternoon nap," I wrote to my mother. "I mean, who does that? Then he'll wake up, go to class, and leave them closed but with the overhead lights on. And of course his bed's unmade, with clothes piled in it." This was my way of saying, "If you expect me to study, I'm going to need to live alone." She heard me, and come spring term I was on my own. Greg would drop by every so often and say, "Nice place."

"Yours could be nice too," I'd say. "You just have to be … have to be …"

The word I was looking for, I'd later realize, was "gay." If you want a room with cinder-block walls to be nice, you have to be gay.

When I first moved to New York, I shared an apartment with a straight guy named Rusty, who was terrific in every respect but one: He liked overhead lights, and would leave them burning even in the daytime. Thus I grumpily lived in my bedroom like a troll, if trolls vacuumed twice a day and regularly washed and ironed their curtains. From the apartment I shared with Rusty I moved in with my boyfriend, Hugh. The two of us have very little in common. Take books. I don't think he's ever read a novel in which one of the characters has a car. With him it's all horse-driven carriages. Or camels. Or elephants painted crazy colors. At the library he goes for whatever has the most dust on it. When he's done he passes it along to his mother, who always loves it just as much as he does. Then they discuss it for hours on end while I sit there dying of boredom. Hugh and I don't agree on music either. Or movies or TV shows. If I think something's funny, he finds it depressing or cruel or, worst of all, "predictable," like he's some comedy psychic and can see everything coming from a mile away.

What we do have in common is an aversion to overhead lights, and on the worst of days I still believe it's enough to keep us together. Every night the candles are lit and placed on the kitchen table. In their glow I can see the person I met almost 25 years ago, young again, and dashing. The effect is even better when I take off my glasses, leaving nothing between him and the eyes I have ruined with a lifetime of reading in the dark. "Is that you?" I'll sometimes ask. "Here, give me your hand." I'd never touch him on the street, I'm just not built that way, but alone together in our beautiful gloom I can see no reason not to.

David Sedaris lives in England and is the author of eight books. His latest, Let's Explore Diabetes With Owls, will be published in paperback in June.